Part two in a series

Part two in a series

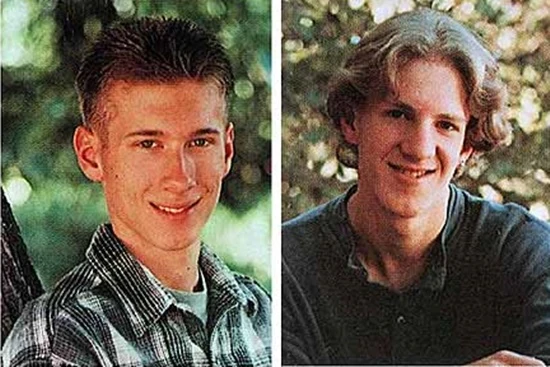

How did it happen? Why did it happen? There’s simply no way to measure how many hours have devoted to these questions in the ten years and four days since Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold opened fire at Columbine High School, and while we don’t (and never will) have all the answers, we do have some of them. Obviously a good bit of the discussion focuses on the individuals themselves, and other analyses cast a broader net, examining the social factors that shaped the individuals. In a way, the question we’re still debating perhaps boils down to nature vs. nurture. Were Harris and Klebold Natural Born Killers? Or are they better understood as by-products of deeper social trends and dynamics?

How did it happen? Why did it happen? There’s simply no way to measure how many hours have devoted to these questions in the ten years and four days since Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold opened fire at Columbine High School, and while we don’t (and never will) have all the answers, we do have some of them. Obviously a good bit of the discussion focuses on the individuals themselves, and other analyses cast a broader net, examining the social factors that shaped the individuals. In a way, the question we’re still debating perhaps boils down to nature vs. nurture. Were Harris and Klebold Natural Born Killers? Or are they better understood as by-products of deeper social trends and dynamics?

The answer is probably “All of the above,” but we can’t simply check C and be on our merry, uncritical way. Checking C isn’t the end of the conversation, it’s the beginning.

Nurture

In the Winter 2000 issue of 49th Parallel, Nicholas Turse (then a doctoral candidate at Columbia), offered up an intriguing theory: that Harris and Klebold were, in some respect, the young radicals of their generation, the Abbie Hoffman and Mark Rudd of the New Millennium.

While these young boys may have no Port Huron statement, no manifesto, and no coordinated actions (that we know of), they are a legitimate radical faction that may have one-upped the violent Weather Underground and the revolutionary Abbie Hoffman. These boys have truly embraced “revolution for the hell of it,” maybe better than Abbie ever did. The randomness of their “non-campaign” may be the ultimate expression of “rage against the machine,” ripping into the system, as it were, at its most vulnerable and fundamental level, perhaps more so than Weatherman’s bombing of the U.S. Capitol.

While these school-age killers have no Vietnam War to protest, and may be criticized by former hippies for having no cause for which to fight, I contend that the struggle in which these boys are engaged may be as fundamentally important as ending the war in Vietnam (or imperialism, or racism, etc.) was to the hippies, Yippies, Diggers, and Panthers of the bygone era. These children, while they do not articulate the sentiment or may not even realize it, are fighting a system as insidious as the military-industrial complex was to their 1960s counterparts. They are fighting the American educational system and, by extension, the so-called American way of life.

I was invited to contribute a response. In my dissent, I suggested that

Turse seems both right and wrong. His suggestion that “kids killing kids may be the radical protest of our age” is most apt (especially given that our age has produced so little in the way of radical protest otherwise). Harris and Klebold represent a contemporary mode of resistance to the dehumanizing character of the American machine, and it is hard to imagine that thirty years from now we will have forgotten the names of those who burned the word “Columbine” into the collective consciousness.

However, instead of Hoffman and Rudd, it seemed to me that the Columbine killers owed more to

the likes of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, as well as to a larger body of neo-Luddites whose discontent with technological society finds voice in the writings of Kirkpatrick Sale, Sven Birkerts, and Mark Slouka. The public mind hasn’t yet put these things together, but I suspect a critical minority will do so eventually. While Harris and Klebold weren’t attacking the machine per se, it’s hard to argue that the monolithic educational infrastructure that helped spawn them is somehow unrelated to the trajectory of technological society generally.

The intent of the killers aside for a second, contemporary society makes it hard for young rebels to find a clear focus:

For starters, millennial culture deprives would-be rebels of both easy targets and productive means of resistance. In the sixties the enemy was easy enough to identify; seemingly all grievances found a handy focus in the Vietnam war effort or the Civil Rights movement, or some combination of both. Youth resistance found clear symbols of institutional evil against which to rally, and thus radical protest was relatively focused. The social and political structure of the era was given to a more or less one-front conflict, with the enemy over there and the rebels over here. The terms of engagement were clear, a fact that dictated and sanctioned certain forms of resistance and ruled out others.

Would-be radicals at the Millennium face a war being fought on a thousand fronts. There is arguably as much or more social evil for a young radical to oppose, but it is diffuse and sometimes intangible. Being ostracized by your high school’s mainstream is perhaps a distressing thing, especially if routine physical harassment by the football team is part of the bargain. When the school ignores the grievance it begins to take an institutional shape. Still, that is a dramatically different thing than seeing friends coming back from Southeast Asia in body bags or watching redneck police turning the dogs on young people who differ from you only in skin color.

Millennial radicals have less obvious targets, and correspondingly their rage finds no moral sanction. The lack of outlets for this anger undoubtedly makes the problem worse—the sixties radical could work these impulses out in a nonviolent fashion that found increasing acknowledgment by the press. Regardless of public reaction, at least they knew someone was listening, a condition that simply did not exist for those unhappy with their lot at Columbine.

Even now, with a decade of hindsight, it’s hard for me to tell how right or wrong I was. We’re in the midst of such dramatic political, economic and technosocial upheaval that I feel like I’m trying to sketch a tornado from inside it.

Others have questioned the role of political and economic factors in breeding the culture from which Harrises and Klebolds might spring, though. Just last week, David Sirota lamented that our national discourse, such as it is, hasn’t “yet matured past gun control and video games.”

In a country that ascribes hubristic “exceptionalism” to itself and berates self-analysis as “hating America,” we seek absolution via scapegoat, and so we upbraid bogeymen like firearms and Xboxes. Similarly, in a democracy increasingly conducting its politics through red-blue filters and 140-character Twitter updates, we crave Occam’s razors — and none are sharper than oversimplified arguments about gun control and video games.

But what about the questions and answers that aren’t so simple? For example, isn’t violence a predictable byproduct of our economy? When torture victims are waterboarded, they freak out. When a winner-take- all economy tortures society, should we be shocked that a few lunatics go over the edge?

For three decades, we converted our economy into one that enriches the rich and stresses out everyone else. Paychecks dwindled, debts accumulated, health-care bills spiked. We now spend more hours working or seeking work, and fewer hours on parenting and rest — all while schools and mental-health services deteriorate.

Sirota is asking important questions here, questions that take us far past “why did they do it?” The deeper question that we have to consider isn’t about the past, it’s about the future – what kind of world are we building and what effect would we reasonably expect it to have on those who grow up in it?There are children in our nation right now for whom the verdict is still out. Their futures have not been decided. If Sirota is right, and if I was right in my fifth prophecy for the 21st Century, some are going to be school shooters. What is happening in their homes right this minute that will make that outcome more or less likely, and what can we do to affect that equation?

Nature

On the other hand… Dave Cullen, who is probably the single best source of journalism on Columbine, characterizes Eric Harris as a stone-cold sociopath.

Harris, who conceived the attacks, was more than just troubled. He was, psychologists now say, a cold-blooded, predatory psychopath — a smart, charming liar with “a preposterously grand superiority complex, a revulsion for authority and an excruciating need for control,” Cullen writes.

Harris, a senior, read voraciously and got good grades when he tried, pleasing his teachers with dazzling prose — then writing in his journal about killing thousands.

“I referred to him — and I’m dating myself — as the Eddie Haskel of Columbine High School,” says Principal Frank DeAngelis, referring to the deceptively polite teen on the 1950s and ’60s sitcom Leave it to Beaver. “He was the type of kid who, when he was in front of adults, he’d tell you what you wanted to hear.”

When he wasn’t, he mixed napalm in the kitchen.

The picture that emerges from ten years of study suggests that perhaps the two killers were necessary elements in a toxic cocktail – a legitimately deranged sociopath in need of a follower and a weak-minded loser willing to be led. Would 4.20.99 have happened had they not found each other? And even given these facts, is there anything that could have been done – thinking back to Sirota’s reasoning above – that could have altered the outcome? Maybe not. And frankly, there’s no way to know, now or ever.

So what to do with the possibility that social context was irrelevant, that some people are born hard-wired for atrocity, that Harris was a genetically flawed Natural Born Killer.

Even if this is true, not all school shooters are Eric Harris. Disturbed, yes. Broken children all, and perhaps broken for different reasons. We still lack enough cases to pull together anything like a representative profile (and with luck it will stay this way). It seems uncontroversial enough to posit that there’s a pool of kids who, depending on the circumstances, might or might not snap. That “snap” might take a number of forms, not all of them harmful to others. But if this hypothesis strikes you as reasonable, it’s probably also not a stretch to suggest that greater stress (in all forms, including the political and economic dynamics that Sirota talks about) might nudge the likelihood of the snap in the wrong direction.

In the end, shootings happen and I fear they will continue to happen. If we knew more than we did we could perhaps better understand the nature vs. nurture question as it applies here. Maybe we’d know whether Harris and Klebold were the rule or the exception, whether the Columbine massacre could have been prevented. Hopefully we’ll someday get to the point where we can answer these questions in ways that decrease the probability of more Columbines.

What we can say, though, is that a diseased body will exhibit symptoms, and that suppressing the symptoms is no substitute for curing the disease.

________________

Previously: The enduring lessons of Columbine

Next: The power of symbols…

Recommended Reading

Dave Cullen, Columbine

Westword Columbine Reader

Salon.com Columbine coverage

Well written piece, Sam, but I don’t know, man. This whole thing about rebellion against abstractions … I’m not sure I can buy it. My best guess (and of course it’s only a guess) is that Harris hated human beings because they were so inferior to him. That’s what some of his writings seem to indicate. He decided they should die. Klebold was more the high school loser type who may grow up to be quite successful, but feels isolated, bullied, and alone. I think those kinds of people come to hate because they feel so abused.

If I were looking for a school shooter type, I wouldn’t necessarily focus on the Harrises of the world. I think they’re very rare. The Klebolds, on the other hand, can be found in large numbers at almost any high school campus. A few of them are bound to pick up a readily available gun and start shooting out of pure anger.

While i cannot say whether Harris or Klebold fit into the rebellion against society as an abstraction, i think that you’re correct in the thesis, Slammy. And such rebellion is particularly dangerous because the outlines of the abstraction are self-described by the rebel.

There are a lot of rebels like that, but no coherent movement because there is nothing tangible to rebel against. The majority of them are not violent. Mostly it seems that this rebellion takes the form of apathy. While the Boomer rebels wanted the right to vote at 18, today’s youth doesn’t even seem to care much about voting. Nor do many of them appear to even be interested in what’s happening in the world.

Futility seems to be the overarching motif. People don’t think that they can stop wars or halt injustice through acts individual or collective. The machine is much bigger and far more dangerous than it was in the late 60’s. Moreover, the police are militarized far beyond what any 60’s radical would have ever seen, and – arguably – far more brutal in every day encounters with the population.

So while the majority keep their heads down, the tiny minority who do commit acts of rebellion are likely to be the most violent and disturbed…and the probable focus will be abstract. Add to this a popular culture dominated by violence and a complete lack of deep thought and we’ve got trouble. Where else is there to go except down? And if you’re going to go down, why not in a blaze of gunfire?

We are hollowing out as a society, leaving the rebels with nothing but echos to reinforce whatever belief they develop…real or self-created. And the response from our soulless society to events like Columbine is simply to clamp down harder, because we want nothing that interferes with our imagined America.

Those kids came through the door of our facade from the back, the place we’re supposed to pretend is not hollow. And the response to someone using that door is to try and nail it shut. Beyond that, we simply generate a lot of fear about what’s behind the facade so that, hopefully, nobody goes back there to poke around. We are – more than anything else – a decadent society motivated almost entirely by fear.

Now watch these same youth start looking forward to an adulthood without much in the way of prospects for getting rich (apparently the only thing that makes you worthwhile in America). See what happens when their friends start coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan psychologically blown apart by pointless war and riddled with cancer from depleted uranium. Imagine how they’ll react to the dawning realization that they’ll need to choose between letting the economy that’s supposed to support them fall or paying through the nose without getting anything in return to cover the excesses of their parents who think its a good idea to borrow from their children to satisfy their own, immediate desires.

I don’t think Harris and Klebold are terrible exceptions to the rule. I think that they were probably outliers and hints of things to come. I hope that i’m wrong, but i’ll bet that i’m not.

Oh, hey, sorry for the dissertation…

Is “crying out just to be heard” similar to what Turse was saying? Even if these two didn’t really have anything they really wanted to say other than, maybe, “something’s wrong” or “I’m not happy?” “Revolution for the hell of it?”

I still tend to put things in terms of forming relationships. More specifically, spreading ideas. Or just communicating.

Could it be that these two felt that they were simply unable to form relationships that were both stable and capable of evolving? Like getting into what they felt were decent colleges. Or making friends or going on dates. Whatever. If they felt stymied at even basic social levels, and truly felt that there was not a damned thing they could do, wouldn’t it make sense that they would have to do something that would break through the walls of their the immediate surroundings? Basically, form a relationship between them (K & H) and as many people as possible (everyone they could reach outside of Columbine). Even if that relationship was hatred or fear or misunderstanding, a relationship would exist that didn’t exist before.

To ensure that that relationship continued and evolved, that act that broke through the walls of their immediate surroundings would have to be dramatic. The more dramatic the event, the more attention they’d get, forming more and more relationships that lasted longer and longer. An event-induced meme, I guess. There isn’t a whole lot more dramatic for a couple of loser high school kids to do than murder/suicide.

(these “walls” may also explain the popularity of Facebook, etc, but that might be a stretch).

Tie that in with nature stuff…

What if we looked at that through a “forming relationships” prism, too. Nature tweaks what individuals consider “important” relationships.

There are the obvious ones…basically everything related to the immediate expansion of the race as a whole (or, at least, an individual’s particular branch of the tree). Most of these tend to be related to some sort of pleasure. Using extreme examples, drug addicts think any relationship that increases the chances of getting more drugs are most important, or nymphomaniacs think relationships that increase the chances of more sex are most important. I don’t think these are all that important in this case.

But then there are the less obvious ones. I’m convinced that there is a family of genes that governs whether or not an individual is self oriented vs. group oriented. On one end of the spectrum, you have the sociopath, or even a prodigy like Mozart. Where everything is in terms of what “I” can do to form “important” relationships with everyone else. On the other end, you have your basic rabid community organizer. What “we” can do to form important relationships. I’d actually argue that you need both sides to move or evolve as a society. Too much “me” and you have too much conflict. Too much “we” and you lose individuality and have stagnation. But that’s another debate.

Combined, yer almost expecting to have something blow up. Obviously, sometimes the extremes can be dangerous as they can be useful. Particularly when you have a case where a sociopath felt walled in.